3. Spatial structures and trends

3.1 Settlement system

There is a general urbanisation trend in all BSR countries. The intensity of this process varies from country to country. But common is a slowing down in the growth of the urbanisation rate. This slow-down may, to some extent, be overestimated, because in the process of sub-urbanisation parts of the urban population are counted as rural.

In Lithuania and Belarus the urbanisation process still contributes to urban growth. In other countries urbanisation seems to have run its course (e.g. Denmark, Sweden, Germany), or has come to a standstill (e.g. Russia, Latvia).

The share of urban in total population in the BSR by the late 90s has reached 73%.

The largest variations on country level are from 62% in Poland to 85% in Denmark and the BSR parts of Germany and Russia. Finland and Sweden lie well above the BSR average with 81 and 84% respectively, whereas Norway, Belarus and the Baltic States have an urbanisation rate between 68-75%.

The relatively large rural population in Poland, Lithuania and Belarus is a potential for future urban population growth.

Differences in urbanisation within BSR countries are significant. In some regions in Latvia only a fifth of the population live in cities. In some Estonian and Polish regions this proportion is just a third. Of the 25 regions (out of 189) in the BSR with the lowest urbanisation rate, 10 are in Poland, 10 in Latvia and 5 in Estonia.

|

Annual average rate of change of % urban population in the BSR 1950-1995

|

|

Sparsely populated areas in the northernmost parts of Norway, Sweden, Finland and Russia are coupled with a majority of their populations living in urban areas.

Though southern Poland in general has a rather high population density, much of this is rural population. The urbanisation rate there is among the lowest in the BSR.

Development of urban structures

All in all, there are 1039 cities in the BSR with more than 10,000 inhabitants17 . Of the 75 million urban inhabitants in the BSR, 63 million live in cities with more than 10,000 inhabitants.

Many regions in the BSR have a high mix of urban and rural populations living close to each other. This offers a potential for rural-urban partnership.

St Petersburg and Berlin dominate. The largest metropolises of the BSR are St Petersburg (4.2 m.) and Berlin (3.4 m.). These two cities serve areas outside as well as inside the BSR. This is also the case with Hamburg (1.6 m.), lying at the interface between North Sea and the BSR.

|

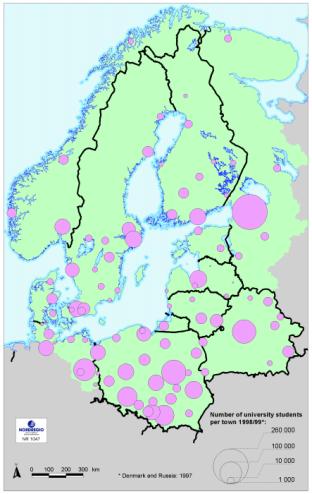

Universities and technical universities in the BSR 1998/99

|

|

|

Source: Nordregio

|

But each of the eleven BSR countries has one or more cities with half a million or more inhabitants. A wide spread of cities with 50,000-500,000 inhabitants reflects a developed urban structure.

A high share of the total population in the northern BSR live in smaller cities. This holds true for Norway, Sweden, Finland. But it also applies to Poland, where nearly half of all urban (>10,000) inhabitants live in cities between 10,000 and 100,000 inhabitants.

Most capital cities dominate their countries as a result of their large relative population size. But this dominance (primacy) differs from country to country, reflecting their different history and territorial composition.

Primacy is pronounced in Latvia, Estonia and Denmark and in BSR Russia, where St Petersburg alone has almost half the total population. The two metropolises Berlin and Hamburg dominate the German part of the BSR. The urban systems of Poland, Lithuania, Sweden and Finland, have no so clearly dominating first city. This also applies to the upper part of the Belorussian urban system. But there the number of lower rank cities is relatively few. The Norwegian urban system is placed in between the two main groups.

Aspects on urban and rural population in the BSR 1998

Education and research centres

Population size gives only limited indication of the functional importance of cities in the BSR. Investments into education and research plays an important role regarding future development. They are crucial for a successful shift to a knowledge-based economy. The geographical location of cities with universities and other higher education institutions also provides a picture of the general (physical) accessibility to knowledge.

Population change in BSR cities>10 000 inhabitants during the 1990s

Several smaller cities are also important centres for R&D, providing education far beyond their actual population or economic activity. This is frequently the result of policies, especially in the 1960s and 1970s, using the geographical dispersion of education as a tool for regional development (for example in Nordic countries and in Germany). In most transition countries, the pattern is more centralised. However, some countries (e.g. Latvia) indicate a rapid growth of institutions for higher edu-cation outside the core areas. These regional educational centres might in the future promote regional development.

Three different trends in population dynamics during 1989-98 are observed18 :

Type 1: substantial population decline in the cities of Murmansk oblast, in most Estonian and Latvian cities, in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern and Brandenburg.

Reasons for this decline differ. In northern Russia and in the new German Länder it is mainly economic. In Germany better employment possibilities elsewhere in the country induced migration. In Estonia and Latvia much of the decline can be accounted for by emigration to Russian and other CIS countries.

In Latvia, some cities (Aizkraukle, Aluksne, Gulbene, Libazi, Madona) have lost the status of cities >10000 inhabitants during the analysis period.

St Petersburg is the city with the largest absolute population decline, having 270,000 less inhabitants in 1998 than in 1989. Poverty led citizens to migrate to rural small settlements around St. Petersburg.

Type 2: substantial growth in areas with smaller settlements around larger cities. This indicates a sub-urbanisation process (urban sprawl): residents of cities move to nearby smaller settlements and commute into the cities.

This is observed for Berlin and Hamburg, for St Petersburg, for large Polish cities such as Warszawa and Lodz, for Tallinn, Riga, Vilnius and Minsk. To a lesser extent this pattern also exists in Copenhagen, Stockholm, Oslo and Helsinki. But there, it has not always led to a similar decline of the city cores themselves.

Type 3: dramatic growth of some large cities, mainly in Belarus, Finland, Norway and Sweden.

Much of this growth is the result of rural-urban migration. In Belarus, Finland and Norway nearly all cities have grown during the 90s.

Urban clusters and functional regions

Cities are important centres of innovation. New knowledge, ideas and products are often introduced in metropolitan regions.

Competition among cities is growing in the globalised economy. This weakens the potential for leading national cities to rely on their national 'home market'. The regional strength gains importance.

The urban regions' competitiveness depends on their internal structure, and is therefore considered as "endogenous".

Endogenous growth, in a knowledge society with dominance of qualified service production, relates as basic resources to education and size of labour market. Size allows a high degree of diversification, and this degree of diversification has become an important indicator for regions' growth potential.

Successful regional/ local clusters may be characterised by:

- qualified labour force

- specialisation in branches located together.

- private and public research & development

- strong local networks between business, research, development, and public institutions, support common learning processes.

- access to financial networks.

- confidence and meeting places.

Within a functional region people are more willing to commute than between functional regions. Empirical evidence suggests that 50 - 60 minutes are a fairly robust approximation of accepted commuting distances.

Improvements in the regional transport system, resulting in a reduction of travel time under 60 minutes, are of great importance for the widening of a local labour market. A reduction of travel time from, say, 85 to 75 minutes will have a much smaller effect.

For the exchange of knowledge, and hence for knowledge-based competitiveness, also the potential to travel between regions is important. Transport system improvements resulting in travel times coming below 2.5 hours are of great significance for the integration between functioning regions. Diminishing of the travel time on a link from 4 to 3,5 hours has a limited effect on this type of integration.

Secondary urban regions

There are indications that urban economic growth in the BSR is increasingly concentrated at a limited number of urban regions 19. In smaller BSR countries/ regions (Baltic States, Kaliningrad region), these are the capital cities. In countries of higher extension, other urban growth centres are developing.

Major urban regions frequently offer better conditions than smaller ones (though there are good counter-examples from non-metropolitan cities, e.g. Poznan in Poland, Tampere in Finland, Aalborg in Denmark) to promote creativeness, to reduce investors risks, to find an open society, to benefit from research institutions, to encounter an innovation climate in public administration and advanced communications infrastructure, and to have access to qualified labour and to diversified services (financial, marketing, trade etc.).

This advantage of major urban centres is further accentuated (particularly in transition countries) by a concentration of foreign direct investment (preferring well-established urban regions), by a concentration of tourism, and of public spending.

Research on economic growth has stressed the role of knowledge and technological spill-over between and within industries. This again favours large cities, where new specialised services from private business find large enough markets.

Such knowledge-intense new small and medium size enterprises (SMEs) are essential for the spreading of new ideas and experiences.

In secondary urban regions, local markets are often too narrow. They must serve customers on more than one local market. Co-operation between cities can promote the competitiveness of local service providers.

Urban-rural relationship

Large BSR sub-regions are beyond commuting distance from dynamic major urban growth centres.

They require sufficiently strong urban centres providing opportunities for dynamic development.

Regions with a high employment share of agriculture and weak urban system

Rural areas, if not located in commuting distance to strong urban centres, are among the more vulnerable elements of the spatial system in the BSR. They suffer from difficulties in giving their populations a proper chance to share benefits from economic and social progress without having to migrate to other regions.

This applies particularly to areas depending almost totally on agriculture or other natural resources exploitation, and where the regional urban systems are not strong enough to develop alternatives.

Then shrinking job supply in agriculture (even if coupled with growing production) is not balanced by growth in other sectors.

In transition countries, the situation varies widely. Where land had been nationalised during the post-war socialist period, and re-privatised during the 90s, different trends occurred: from conversion into large private agriculture enterprises (e.g. in German New Länder) through fragmentation into small farms of, sometimes, only subsistence size (e.g. in parts of Baltic States) to wide-spread abandonment (with retired couples growing some fruit and vegetables, holding maybe one cow).

In parts of Poland, where private farms were maintained, small-sized farms continue to exist which can hardly compete on a liberalised market. In Belarus, state-owned farms continue to exist, but get under growing pressure to rationalise labour input.

From spatial development point of view, four basic situations (with combinations) exist:

Rural areas with relative high population density (compared with average rural areas) but a weak urban system, living mostly on agriculture and some food processing.

These areas face reduced job supply as a consequence of production modernisation. Either they develop alternatives of corresponding significance, or they loose population. This may create growing spatial imbalances. Main areas affected by this trend will be some of EU accession countries, with a concentration in south-eastern Poland.

Rural areas with low population density, high reliance on agriculture (and some food processing) and weak urban system.

These areas are also facing reduced job supply with the process of modernisation, but have even more difficulties to develop new sources of employment. Such areas exist in wide parts of the BSR.

Peripheral areas in Nordic countries living basically on natural resources (forestry and - mainly in Norway - fishery), having urban centres with some potential of development. Rural population density is low, job supply stagnant at best, and services supply to the population depends on a relatively high level of State subsidies.

Rural areas in commuting distance of dynamic urban centres

These zones tend to develop into urban sprawl areas with a loss of clear lines between urban and rural space. Their problem is not a lack of job supply in non-agricultural sectors, but loss of cultural and natural landscapes.

Sustainable spatial structure of urban regions

The sustainability of urban development is threatened by several trends, in transition as well as in other BSR countries.

Multi core urban structures

There is a tendency for decentralised growth in metropolitan regions. Households start to move out, jobs gradually follow within services related to the growing population and later also other types of jobs. The challenge is to manage this growth to avoid suburbanisation and urban sprawl.

Urban sprawl is characterised by spatial expansion of cities, reduced density, growth of individual vehicular traffic and retreating public transport.

Negative effects of urban sprawl are environmental degradation, growing land-use for parking and for street areas, invasion of valuable landscapes, rising cost of infrastructure and public services supply, loss of urban identity and attractiveness.

Large shopping centres often flourish in the suburban areas, relying on accessibility by private cars. In some countries, e.g. Denmark, Germany, spatial policies try to limit the trend for such new shopping areas.

Urban sprawl is often coupled with inner city dereliction, due to low private investment into central locations: population, consumer services, and later also offices move away. This may turn into a downward spiral.

Multicore urban structures can contribute to avoid negative forms of urban sprawl. They are more efficient, from economic, social and environmental viewpoints, than mono-centric urban structures. Multicore urban structures are related to accessibility in the networks for transport. Rail transport favours concentration. Accessibility only by cars favours a dispersed structure.

Urban management is needed to promote liveable cores with urban qualities and broad businesses clusters. If the urban change process is left totally to the market, new cores tend to become too small.

Urban regions in transition countries have the advantage of a concentrated settlement structure and well developed networks for public transport. But by being mono-centric instead of multi-core, they run an even higher risk of urban sprawl than major cities in north-western parts of the BSR. Financial restrictions tend to support this negative trend by promoting 'cheap' short-term instead of cost-effective long-term measures. Thus, the development of multi-core structures is urgent if the advantages of concentration and strong public transport systems are to be maintained.

Urban renewal

In metropolitan areas, which have restored and modernised older parts of the inner city, more people choose to live in downtown locations and not to own (or not to use so often) a private car.

Also many smaller cities offering a pleasant environment within commuting distance from metropolitan centers, attract people.

The same applies for businesses. Their choice of location is often a matter of trade-off between benefits from a well-accessible location for staff, customers and cargo delivery, and the cost related to land value and rents.

Several BSR cities are now redeveloping areas in attractive inner-city locations, including former harbour areas.

Challenges regarding the settlement system

- Raise the competitiveness of urban regions;

- Counteract growth concentration at too few urban centres.

- Strengthen functionality of cities as growth engines in rural areas;

- Promote integrated rural development which joins urban and rural elements and which links different sector measures

|

There is, however, also a trend towards loss of urban qualities. Valuable urban ensembles loose attractiveness, open spaces are converted into parking areas, roads are widened, and modern buildings replace traditional ones.

Social integration

Urban areas loosing investors' and residents' interest and coming into the downward spiral are to a growing extent inhabited only by the poor. Social segregation is often combined with a spatial separation between people representing different cultural backgrounds. A consequence is growing instability of urban societies.

Segregation is a "burning question" in many cities20 . Several types of actions must be combined to break negative trends in less attractive areas, including:

- partnerships between various types of public, private and non governmental organisations;

- long-term commitment based on local participation;

- improved housing standards and urban qualities;

- improved accessibility to jobs and education also for women;

- cultural diversity;

- education and training in future orientated branches.

Challenges regarding urban structures

- Move from mono- to multi-core urban structures which combine decentralisation with strong public transport systems;

- Promote sustainable internal urban structures.

- Counteract urban sprawl into valuable landscapes;

|

Degradation of big housing estates

Large housing estates built during past decades, particularly (but not only) in transition countries, are rapidly loosing attractiveness. Many of these suffer from low technical standards and lack of maintenance.

Most prominent is the example of eastern Germany, where up to one million housing units are facing demolishing, because populations moved to other cities (offering better jobs), to upgraded inner city locations, or to new individual housing areas.

Remaining populations cease to be well supplied with public and private services. This accelerates social segregation.

Best practice often combines investments to improve technical standards and the local environment with a mobilisation of local inhabitants.

Various efforts are made in the transition countries. In St. Petersburg, the city tries to attract private investors to rebuild the houses at their own expense, by giving access to attractive land for new exploitation. This strategy is faced with incomplete market reform and deficient regulatory and institutional frameworks.